Module tf.about.annotate

Named Entity Recognition

Entities

An entity is a thing in the real world that is referenced by specific pieces of text in the corpus. Think of persons, places, organizations.

We mark up those text occurrences by creating nodes for those locations in the corpus

and assigning feature values to the features eid (entity identifier) and kind

(entity kind such as PER, LOC, ORG).

We also make nodes for the groups of occurrences that have the same eid and the

same kind. So entity nodes stand for individual persons, places or organizations,

and ent nodes stand of single occurrences of them in the corpus.

Occurrences and identifiers

ent nodes mark the text occurrences that refer to outside entities in the world.

Different occurrences have different entity nodes, but they may refer to the same

entity in the world. It is the entity identifier in combination with the kind of entity

that unifies the various occurrences that refer to the same entity in the world.

entitycorrespond 1-1 to the real world entities.

The same occurrence may have multiple ent nodes.

For example, if an occurrence Amsterdam refers to a location, a city council,

and a ship at the same time, you might mark it up as

('amsterdam', 'LOC')('amsterdam', 'ORG')('amsterdam', 'SHIP')

Here you see that an entity in the real word is not solely identified by the

eid feature, but by the combination of the eid and kind features.

Of course, you are free to make the identifiers distinct if the same name refers to entities of different kinds.

How entities exist in a corpus

Your corpus may already have entities, marked up by an automatic tool such as

Spacy, see

tff.convert.myspacy.

In that case there is already a node type ent and features eid and kind.

When you make manual annotations, the annotations are saved as TSV files.

In order to create nodes for them in your corpus, you can use those TSV files,

to bake the corresponding ent and entity nodes into your corpus.

See NER.bakeEntities()

Entity sets

When you are in the process of manual marking entities, you create an entity set. You can give this a name, and the data you create will be stored under that name.

Sheets

When you start by writing a spreadsheet with names, kinds and triggers and additional

entity metadata, TF can read that, and it will create a name for the entity set

based on the name of the spreadsheet, and preceded by a .. TF will recognize

these sets as belonging to a spreadsheet as opposed to a manual annotation set.

What kind of NER detection does TF support?

Named Entity Recognition is a task for which automated tools exist. But in a smallish, well-known corpus, such tools tend to create more noise than signal. If you know which names to expect and in what forms they occur in the corpus, it might be easier to mark them by means of a set of triggers, or even by hand.

TF contains a tool to help you with that. The basic thing it does is to find all occurrences of a set of patterns you specify, and then assign identifiers and other attributes to all occurrences of those patterns.

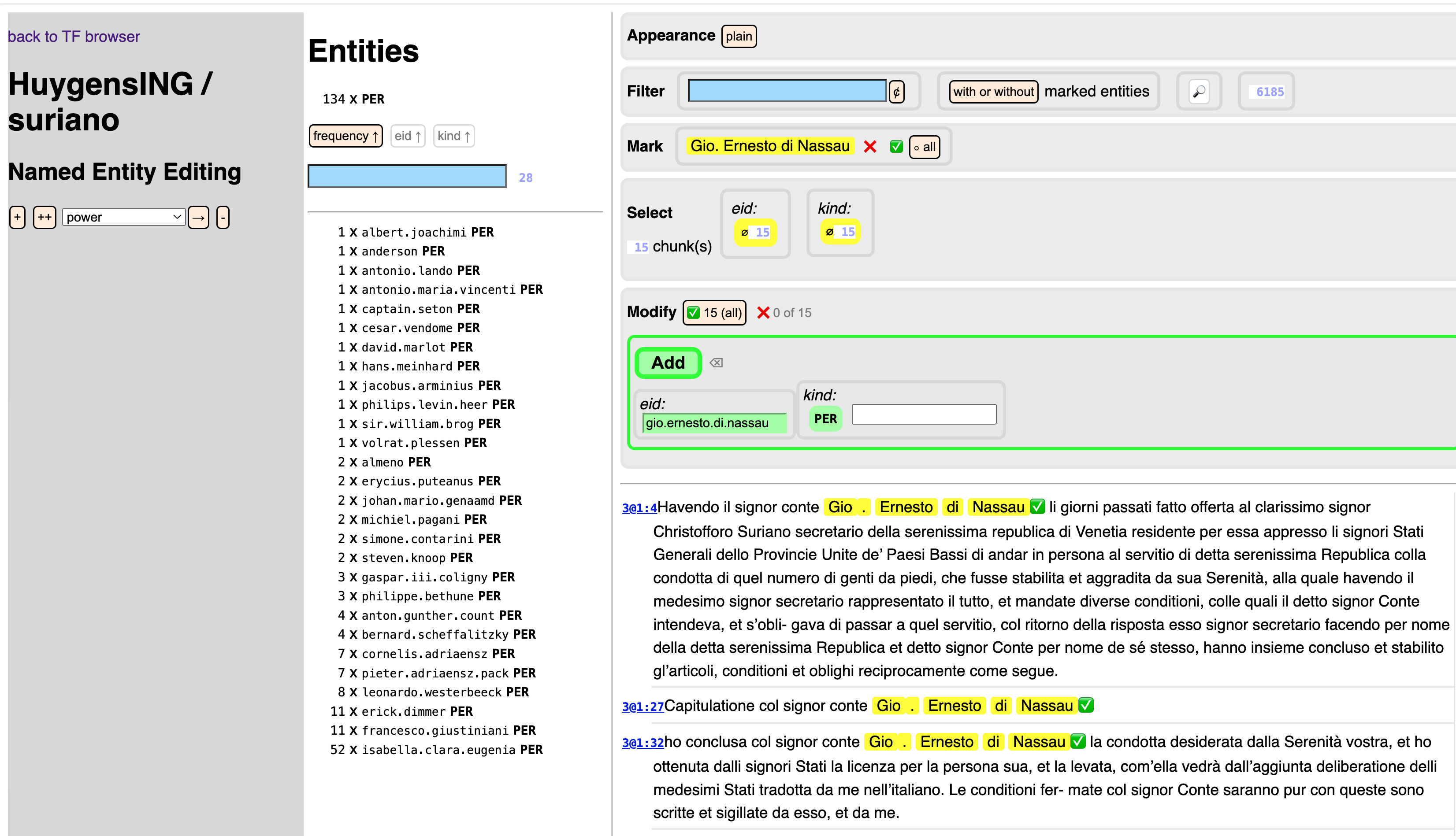

For example, it finds all Gio. Ernesto di Nassau occurrences and it assigns

identity gio.ernesto.di.nassau and kind PER to them.

There are two interfaces:

- a spreadsheet for bulk assignment, operated from a Jupyter Notebook or

Python program; see

tf.ner.ner - the TF browser for inspection and manual assignment of entities;

see

tf.about.annotateBrowser

How do you tackle NER with TF?

The recommended scenario is this:

- prepare a spreadsheet where named entities are linked to triggers;

- TF can load such a spreadsheet and find those entities in the corpus;

- TF will check the spreadsheet for various mistakes, and reports on the outcomes;

- Depending on the reports, adapt the spreadsheet and load it again;

- Optionally run a program to find spelling variants and add them to the spreadsheet;

- Check the variants and put the wrong ones in an exception list;

- Use TF to merge the variants with the original triggers into a new spreadsheet;

- Load the merged spreadsheet;

- Check the reports and adapt the original or the merged spreadsheet;

- Iterate until the outcome is optimal, use the TF browser to inspect special cases;

- Optionally use the TF browser to add/delete individual entity occurrences;

- Use TF to bake the entities with the corpus into a new TF dataset.

However, you can also start right away in the TF browser and build up entity sets by hand.

See

tf.ner.nerfor how to work with spreadsheets;tf.ner.variantsfor how to add spelling variants to spreadsheets;tf.about.annotateBrowserfor how to work with the browser interface. Here is what the browser interface looks like:

How do I prepare my input?

There are several bits of information needed to set up the annotation tool. They are corpus specific, so they must be specified in a YAML file in the corpus repository.

You need:

- a configuration file

config.yamlin the directorynerof your repo; seeSettings - one or more spreadsheets in the directory

ner/specsof your repo; seeSheets.readSheetData()

As an example, we refer to the Suriano/letters corpus.

How well does it work?

We applied this method on the corpus of letters of Suriano, using a spreadsheet with over 700 named entities and over 2000 triggers leading to 12,500 marked entities.

TF is performant, it looks up all those triggers in one pass over the corpus. Later, when it diagnoses the outcome, it needs to search for those triggers in isolation because triggers may interfere with each other in unexpected ways. TF will then search for them in as few passes over the corpus as possible.

Is it subtle enough?

It is quite common that a trigger stands for various entities depending on the context.

For example, il papa (the pope) may refer to one person when it occurs in a letter of

1617, and another person when it occurs in a letter of 1620.

TF allows scoped triggers: for each set of triggers you can supply a scope, in the form of ranges of sections for which the trigger should be looked up.

There is also an implicit rule that no piece of text falls under two entities. When two triggers fight for a match, the trigger that has the match that starts earlier wins. If they start at the same spot, the longer trigger wins. Because a longer trigger is more specific than a shorter trigger.

Yet it is quite an art to fill such a spreadsheet with triggers, and some trial and error is needed. TF helps with that in two ways:

- it provides a lot of feedback on problem cases;

- the process of loading a spreadsheet, searching for the triggers, and producing reports takes only a few seconds.

Is it generic?

Yes. It only makes use of those characteristics of a corpus that it can glean from the TF dataset. If your corpus is in TF, these methods will work.

However, as the software is not yet completely mature, it might be the case that you bump into some details that will conflict with the characteristics of your corpus.

Currently I am not aware of corpus-dependent issues, though.

See sections()

How exactly are the entities delivered?

-

As additional non-TF data accompanying a TF dataset; you can find it in your repo, in directory

_temp/ner/version/.name-of-set; in there is a file data.gz which contains zipped pickled data described intf.ner.data; based on this data you can see the entities displayed in your corpus in the TF browser and you can also show them in a Jupyter notebook, or treat them in an arbitrary Python program. -

You can bake an entity set into the TF corpus. When you do this, a new TF dataset will be created for your corpus, with new nodes for entities and entity occurrences and features for entity id and entity kind.

N.B.: in order to perform this operation, you have to do it in a Jupyter notebook or a Python program.

-

There are also less hidden results in the same directory:

-

entities.tsv: each line corresponds to an entity occurrence, it has columns for the entity id, the entity kind, and one column for each slot the occurrence occupies in the TF dataset;

This is the file whose information is used to bake the entity information into a new dataset.

-

-

If you have produced the entities by means of a spreadsheet with triggers, you see in the same directory the following files:

-

hits.tsv: each line corresponds to a number of hits and has the fields:

- label: indicates the succes of the trigger

- name: the entity that this trigger belongs to

- trigger: the trigger that produced these hits

- scope: the scope of the trigger (the sections in which it is activated)

- section: the section in which the hits occur

- hits: the number of hits in this section

This file is mainly meant to check and debug your triggers and scopes.

-

triggerBySlot.tsv: each line corresponds to a slot that is part of a result of a trigger. The columns are:

- slot: the slot number

- trigger: the trigger that correponds to the hit of which the slot is a part.

Note that a all hits are disjoint, and that a hit can only belong to one trigger.

-

interference.txt: reports on the interference between triggers. Only triggers of different entities that have actually interfered.

-

Supported corpora

This tool is being developed against the

Suriano/letters corpus.

Yet it is meant to be usable for all TF corpora. No corpus knowledge is baked in.

If corpus specifics are needed, it will be fetched from the already present TF

configuration of that corpus.

And where that is not sufficient, details are put in ner/config.yaml, which

can be put next to the corpus.

These corpus-dependent traits are collected by the module tf.ner.corpus and the

rest of the program uses those traits through this module.

I have tested it for the ETCBC/bhsa (Hebrew Bible) corpus, and the machinery works. But it remains to be seen whether the tools is sufficiently ergonomic for that corpus.

See also the following Jupyter Notebooks that show the work-in-progress:

-

Suriano

-

BHSA

For corpus maintainers

This tool needs additional input data and produces additional output data.

The input data can be found in the directory ner next to the actual tf directory

from where the program has loaded the corpus data.

Depending on how you invoke TF, this can be in a clone of the repository of the corpus, or an auto-downloaded copy of the data.

If you work with the corpus in a local clone, you'll find it under

~/github/HuygensING/suriano (in this example).

If you work in an auto-downloaded copy of the corpus, it is under

~/text-fabric-data/github/HuygensING/suriano (in this example).

Note that

- the part

githubmay be another back-end in your situation, e.g.gitlaborgitlab.huc.di.nl; - the part

HuygensINGmay be another organization, e.g.annotation, or wherever your corpus is located; surianomight also be another repo such asdescartes, or where ever your corpus is located.

The output data can be found a directory _temp/ner where the _temp

directory is located next to the ner directory that holds the input data.

Good practice

All NER input data (configuration file and Excel sheets) should reside in the

repository.

The corresponding TF app should specify in its app/config.yaml,

under provenanceSpecs:

extraData: ner

When you make a new release on GitHub of the repo, do not forget to run

cd ~/github/HuygensING/suriano

tf-zipall

Then pick up the new ~/Downloads/github/HuygensING/suriano/complete.zip

and attach it to your new release on GitHub.

Then other users can invoke the corpus by

A = use("HuygensING/suriano")

This way there is no need to clone the repository first.

TF will auto-download the corpus, including the ner input data.

Then multiple people can work on annotation tasks on their local computers.

Output data

The results of all your annotation actions will end up in the

_temp/ner/version folder in your corpus, where version is the

TF version of your corpus.

The output data is tightly coupled to a specific version of the corpus.

Versioning

If a new versions of the corpus is published, the generated annotations

do not automatically migrate to the new version.

TF has tools to perform those migrations, but they are not fully automatic.

Whenever a new version of the corpus is produced, the producer should also

generate a mapping file from the nodes of the new corpus to the old corpus.

That will enable the migration of the annotations.

See tf.dataset.nodemaps .